Silicon Intelligence and Carbon Wisdom

Defending a Generative Constructal PhD at Imperial College London

At the beginning of February 2026, I defended my PhD thesis at Imperial College London. My examiners were Prof. Umit Gunes from Yildiz Technical University and Prof. Guillermo Rein from Imperial. My supervisor, Prof. Ricardo Martinez-Botas was patiently auditing the conversation.

The Thesis: Generative Constructal Design

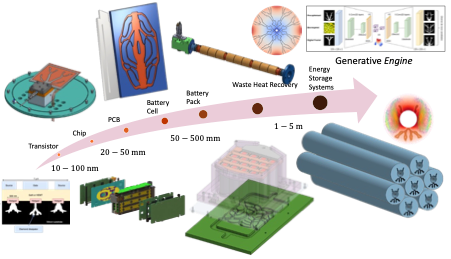

The thesis advances thermal design by unifying evolutionary principles with generative methods. Rooted in the Constructal Law — that systems evolve to facilitate easier access to what flows — the work proposes a methodology for designing thermal systems that are free to morph under changing physics and constraints.

The framework combines:

evolutionary search,

generative methods,

and finite element multi-physics solvers

to learn a low-dimensional, navigable representation of flow architectures.

Unlike biomimicry, which is descriptive, or parametric methods, which are prescriptive, this approach is predictive: it reveals not only efficient configurations, but how architectures evolve when demands change.

Across four classes of systems — conductive heat sinks, hierarchical thermal metamaterials, waste heat recovery channels, and battery cooling networks — the designs evolved in silico exhibited a persistent tendency toward improved access and reduced global resistance.

Some highlights:

Up to 13% multi-objective performance improvement over state-of-the-art gradient-based optimisation, with 6× faster convergence [1].

Multi-objective thermal cloaks generated in under five minutes on a standard workstation [2].

35% heat transfer enhancement in pulsating convection experiments [3].

37% hotspot reduction and 50% pumping power reduction in battery cooling compared to parametric straight-channel designs.

Notably, all designs were generated on consumer-level hardware: a small gaming PC that cost less than $1,000.

The viva itself lasted a few hours; the journey behind it began more than 20 years ago. In many ways, the defence was not just about thermal systems, generative models, or evolutionary design. It was an opportunity to connect the dots of a development path that started when I was 5, sitting across a chessboard, trying to see three moves ahead.

Chess: Flow in Multiple Dimensions

Training as a competitive chess player taught me something that later resurfaced in my professional career: progress depends on discipline, freedom and access.

In chess, you assess a position not only in the present, but in the space of future possibilities. You ask:

Which pieces have mobility?

Which paths are blocked?

Where is resistance accumulating?

A good position is one that improves access — to squares, to tempo, to initiative.

Constructal theory expresses this principle physically

For a finite size flow system to persist in time (to live), it must evolve with freedom such that it provides easier and greater access to what flows.

I did not know the Law when I was five, but I recognised the pattern.

Chess also taught me something equally important for research: how to lose. To analyse defeat without resentment, and move on. Move on quickly, the next game is tomorrow. And wasting time dwelling on the past is only useful for my next opponent.

I did not have a long Chess career, I quit at 11, when I found something more interesting.

Mathematics: Elegance Is Not Optional

Participating in national Mathematics Olympiads reinforced another lesson: representation is everything. A problem rarely becomes easier by brute force. It becomes easier when expressed properly, in simple terms. Just like in chess, a solution (i.e., the path to victory) is made by putting together the building blocks that you acquired in training. It is solely up to you to see the pattern.

Elegance is not aesthetic luxury — it reduces cognitive load and clarifies structure. This insight later guided my approach to design optimisation. Instead of repeatedly solving large PDE-constrained problems, could we find a representation that makes the search itself simpler?

Could we compress the space of feasible flow architectures into something continuous and navigable?

That question ultimately led to the generative framework developed in my thesis, now called DendrON. One that is both informed by nature (carbon wisdom) and enabled by machine learning (silicon intelligence).

Living and non-living: No Artificial Barriers

While me relationship with mathematics is not as short-lived as my Chess career, I kept finding more interesting things to preoccupy myself with. Here, I have to pay tribute to my family, who insisted that I avoid falling into the trap of playing video games on ever smaller screens, ultimately encouraging me to take up reading instead.

Physics and Biology where among my favourite subjects, and I trained for a couple of years to become a medic. While keeping my options open by studying Engineering, I became fascinated by the continuity between the so-called living and non-living systems.

People and engines breathe; hearts pop up in mammals, but also in complex analysis; neural networks are useful in brains and computers — the patterns repeat. The physics is shared. The differences are contextual, not fundamental.

Years later, when already in London, Constructal theory provided a language for this unity. It dissolves the artificial barrier between animate and inanimate structures by focusing on flow, and allowed me to put 1 (physics) and 1 (biology) together.

Photography: Saying More with Less

Photography entered as a hobby but became unexpectedly formative. Like most teenagers, I didn’t like how I looked at the time, so I hid behind a camera.

To take a good photograph is to:

decide what to include,

what to exclude,

and how to use limited resolution to emphasise the main carrier of information.

Post-processing sharpened this awareness. A photograph is not just captured — it is revealed.

Working with generative models later felt strangely familiar. High-resolution geometries were compressed into low-dimensional latent spaces. The question was not how to store everything, but how to preserve what matters. Learning to see an image “through the eyes of the mind” is not very different from learning to see a design before it fully materialises.

Freedom and Discipline

Throughout my PhD, one theme resurfaced repeatedly: Freedom. Freedom in design means degrees of freedom — allowing geometry to change, configuration to adapt, structure to emerge. Freedom in research means resilience and the liberty to take up new problems, out of the so-called comfort zone.

Yet Freedom without Discipline collapses into noise.

One of the greatest lessons I learned from my supervisor, Professor Ricardo Martinez-Botas, is that freedom and structure are not opposites. They are partners. Discipline gives direction to freedom; freedom gives purpose to discipline. Constructal theory itself reflects this duality: constraints are not obstacles; they are the reason form emerges.

Endurance and Setbacks

Research, like sport, is less about intensity and more about consistency. I was fortunate to spend the summer before my graduate studies in Croatia, working for Rimac Technology in Zagreb. While completely alone, in a new country, I started training judiciously. Every day.

The conditioning I managed to complete there allowed me to take up new sports, roughly every year: cycling, running and swimming. During my PhD, I swam more than 500 km, ran and cycled more than 1000 km (each). These numbers are insignificant in athletic terms, but they hide behind something important: learning to go through setbacks without drama.

Papers rejected. Experiments delayed. Rigs breaking before a deadline.

Sport teaches you to keep moving.

Connecting the Dots

Looking back, the defence was not simply a technical milestone. It was a moment of convergence:

Chess taught multi-dimensional thinking.

Mathematics taught elegant representation.

Physics and Biology revealed unity across systems.

Photography sharpened perception and compression.

Engineering provided impact.

Sport built resilience.

The Constructal Law offered a unifying principle. The thesis did not optimise for rigid objectives, nor did it search for the end-design. It explored how we search for new configurations, at the border of chaos and order — how architectures evolve when given freedom to morph under physical constraints.

If systems persist by improving access, then perhaps research careers do too.

I am deeply grateful to the mentors, colleagues, friends who made this journey possible. I thank Prof. Adrian Bejan and the Constructal community for providing the intellectual compass.

I am forever indebted to my parents, Daniela and Claudiu, for fostering my moral compass and a growth mindset (before it was fashionable). I thank my sister, Iasmina, for being the perfect sparring partner (albeit a sore loser).

This is not the end. It is the end of the beginning.

About the author

The author was born on 19 December 1999 in București, România. He graduated from Colegiul Național de Informatică “Tudor Vianu” in 2018, and moved to the U.K. to study Mechanical Engineering at Imperial College London.

Matei graduated with an MEng in June 2022 and received his PhD in February 2026. He was recently awarded the Dr Ashraf Ben El-Shanawany Memorial Prize for the best PhD student, with outstanding achievements in research, public outreach and innovation.

His peer-reviewed publications include:

[1] Matei C. Ignuta-Ciuncanu, Hannes Stärk, and Ricardo F. Martinez-Botas. Evolutionary design of conductive pathways using a generative autoencoder. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 166:109098, 8 2025.

[2] Matei C. Ignuta-Ciuncanu, Philip Tabor, and Ricardo F. Martinez-Botas. A generative design framework for passive thermal control with macroscopic metamaterials. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, 51:102637, 2024.

[3] Matei C. Ignuta-Ciuncanu, Jordan Michael, Shuyang Qian, Chris Noon, and Ricardo F. Martinez-Botas. Experimental characterization of heat transfer and fluid dynamics in pulsating exhaust flows. Journal of Turbomachinery, 148(3):031012, 10 2025.

[4] Matei C. Ignuta-Ciuncanu and Ricardo F. Martinez-Botas. Discrete svelteness: Evaluating flow structures in generative constructal design. BioSystems, 105459, 4 2025.

[5] Matei C. Ignuta-Ciuncanu and Ricardo F. Martinez-Botas. Evolutionary design of radial fins for forced and natural convection using generative methods. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 171:110027, 2026.

[6] Matei C. Ignuta-Ciuncanu, Chris Noon, and Ricardo F. Martinez-Botas. Heat Transfer Enhancement in Pulsating Flows: A Bayesian Approach to Experimental Correlations. Journal of Turbomachinery, 147(5):051009, 11 2024.

[7] Matei C. Ignuta-Ciuncanu, Philip Tabor, and Ricardo F. Martinez-Botas. Constructal Law, Biomimicry, and Topology Optimization Through The Lens Of Generative AI. 14th CONSTRUCTAL LAW CONFERENCE — 10-11 October 2024, Bucharest, Romania, 2024:41–44, 12 2024.

[8] Matei C. Ignuta-Ciuncanu, Philip Tabor, and Ricardo F. Martinez-Botas. Generative constructal design of a multi-physics heat sink for managing transient thermal loads. ASME Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, pages 1–21, 10 2025.

[9] Philip Tabor, Matei C. Ignuta-Ciuncanu, and Ricardo F. Martinez-Botas. Thermal diodes, transistors and logic: Review of unconventional computing methods. BioSystems, 105491, 6 2025.